When I read headlines like “Congress clinches $1.2T funding deal for DHS, Pentagon, domestic agencies” and “Democrats support bill that would give ICE $10 billion” and “Jeffries won’t whip vote against ICE funding.” just weeks after Jonathan Ross, a longtime ICE firearms instructor, literally filmed himself shooting Renee Good in the face, I’m sorry, the party has lost me. Unless leadership turns over – Mamdani! AOC! Bernie! Eliabeth! – or unless a new party figures out a blueprint for regime change, I’m left in the dark, lost in the shadows, fantasizing the end of the world as I know it. As a Jew with ancestors plucked off the streets by an armed, masked gestapo, I’m sensitive to history repeating here, in my country, and shortly in my state (as goes Maine, so will go Vermont. What will Scott do? I can guess. ) Jack Smith laid it out, our former president was a felon. So? We elected him again. Of course, not me, but “we” in the sense of “us” not criminalizing him after January 6th. I wonder how my party let Smith be gagged and himself open to conviction. I have no solutions, I’m not a politician. It’s not my game. I did my marching in the ’60’s and am too old now to chase armed goons in the street waving my broom against a rifle as if one could sweep away the yellow filth blasted in the eyes of a helpless citizen. It’s a dilemma: on the one hand I’m filled with awe of my beautiful spinning planet, on the other hand I’m terrified as one species, mine, seems determined to wipe it all out. Yes, I have with me the artists, the poets, the caretakers, GenZ and maybe five of the governors, but our voices are marginalized by the uncanny reluctance of those we elected to protect us. All I have is one voice, however thin, to add to the millions raging against the machine. But for us to be heard, we need our party. We elected you. Fear isn’t an option.

Vermont Studio Center

After experiencing one of those life changing events that slam down without warning. I moved in a daze into a South Burlington condo with my dog and I found I could not write a coherent sentence. What I needed was to immerse myself in a dedicated community, no distractions, no meals to cook, dogs to walk. And – thank you fate – I was accepted at the Vermont Studio Center in Johnson, full fellowship, with a sweet suite to live in, a separate studio, great food and a vital, community. You could work all night, take meals at the commuter and interact as much as you wanted, no pressure.

I brought with me the novel I was working on. Technically, it was the middle of a second draft, but I was wrong. Time had gone by, my world and The World had ruptured, (e.g January 6th, the Trump election, floods, wild fires, species extinctions) and my characters had to be as crazed by all this as I was, something deeply human was ending, the end of the world as we knew it was no longer a concept, it was in process, we were in a dystopia, headed into trouble everywhere. My characters were still yapping away in my head, but now I was listening deeply, instead of imposing a story on them to navigate.

So what if I imagined a scenario where the worst was happening and planted my characters there. I had recently published a short story, very different than anything I had done before, it was speculative fiction, an actual genre, with a newly driven voice. So, what if I planted my characters in this world that was really dissolving. That I felt was pushing humanity in a direction we/they might not be able to navigate. So many questions, no answers, and that felt right. Asking those questions, I got it, I needed to start in a very different place and figure out how the people in my head were going to move through towards an ending, one that had always been clear in my mind but now was much more deeply loaded.

That week was like a em dash –––it led to a summer in a cabin by the lake, writing and reading and waking up. Whew.

Read Like A Writer, again.

Meeting the 2nd and 4th Monday of each month with Riki Moss at 6:30 – 8PM ET via Zoom Workshops are free, no adm to wade through: just email riki@nereadersandwriters.com for the files and Zoom link.

Why should writers read? Faulkner tells writers to “…read everything, just like an apprentice who studies the masters. Read! You’ll absorb it. Then write. If it is good, you’ll find out.” As Zen master Dogen said, “If you walk in the mist, you get wet.”

Fiction writers might be liars, fictionalizing names, places, ideas – and we all are wary of the reliability of memory – but when fiction is in service of deeper truths, we know it, we want to learn how the writer did it, we want to explore for ourselves.

Here’s the schedule from September through the end of the year:

9/8 Grace Paley: Conversations with my Father plus a forward from George Saunders who worked through this story on his substack. George loves Grace, whom he calls one of the great masters of our time. Here’s an opportunity to find out why, how to think about the larger import of her work, what questions she raises that are significant to any fiction writer. We’ll follow Saunders as he moves through the story.

9/22 David Means: Means is sterling in his chosen turf, “the great desolate span of the Central states,” and he’s also interesting as a male writer about relationships. The style is intriguing, no quoted dialogue, long paragraphs with little punctuation working between fact and fiction, poetics/God and hard reality. We’ve read two of his stories previously, but he just keeps going deeper with some structural quirks that are deviously fascinating.

10/13 László Krasznahorkai’s An Angel Passed Above Us published recently in The Yale Review has a hash tag: “The novelist of apocalypse insists on the reality of the present.” Remember that his earliest work was grounded in a Hungary suffocating within the Iron Curtain: later he found a relative lightness of being with books like “Seiobo There Below.” In this story, he contrasts the muddy trenches of the war in Ukraine with the phantasmagoric promises of technological globalization. He’s won the Booker, is always a name that comes quickly to mind for the Nobel and he is one of the most elegant writers of our time.

10/27 Jason Mott: an excerpt from his fourth Novel, One Hell of a Book, where an African-American author sets out on a cross-country book tour to promote his bestselling novel. I know, we want to avoid excerpts, AND memoir AND auto fiction but this guy has a wholly original voice that we need to hear and besides, he won the National. Big lessons in dialogue, big distinction between Mott’s loose patois vs the tightly sublime verbiage of both Means and Krasznahorkai.

11/10 Aimee Bender: Off a first person narrative by a willful, nuts, predatory, annoying woman messing up a party for her own game plan. A little surrealism, a little reality and a lot of sass. Bender gives us an unlikable female character with vulnerability right under the surface. A number of female authors are writing like this today, letting the ladies screw things up without judgement or redemption: I see resonance with Colette, Lucia Berlin, Mary Gaitskill, even Clarice Lispector.

11/24 Sequoia Magamatsu: Pig Son. A scientist cloning pigs for their organs gets caught in a serious conundrum when this pig starts talking, because his own child died of a diseased heart. There’s a bit of Ishiguro here: think of his novel Remains of the Day, a story about children raised to be donors. A simply written story by a young American-Japanese, whose latest novel, How High We Go In The Dark isn’t exactly sci fi or speculative fiction – let’s be unencumbered by genres here. The writing is simple, the idea complicated and we can consider how we would write in the POV of a non-verbal animal (or river or mountain).

12/8 David Foster Wallace: excerpt from The Pale King called Good People. This stands alone as a complete story. An Ironic title? Is DFW questioning what’s “good”? He’s tight in the head of his male character who tries to understand his lovers’ predicament and his place in it, It’s a moral question that will impact their lives deeply. “He was desperate to be good people, to still be able to feel he was good.” The writing is pure DFW, deep, insightful, fearless.

12/22 Flash. We’ll end 2025 with a burst of Flash, TBA.

Fiction wins

I’m deeply involved in a writers community in my city. It’s a Meetup group that has maybe 200 active members. When the founder disappeared (who knows the real story behind this), they (who are they?) formed a 501C3 that required a Board, so that was formed, and after their terms ran out, a second Board came forth but a year later almost all of them quit in a huff without telling anyone why, without a transition plan. Then a transitional team tried to form, but they too quit (what is it with quitting boards?) and now there is an emergency community meeting because we have to pay the rent.

This has been going on for months, and now half of us who used to be copasetic in community don’t speak to the other half: being writers, we started sending each other overly long, acrimonious, analytical and philosophical emails and neglected our own novels.

I unapologetically fled. I was able to get out of town to a residency where I determined to convince my novel to forgive me.

I’m thinking of something that happened to a famous writer whose name I’ve forgotten. She tells the story of having thought of writing a novel about – I’m quoting from Amazon here – “a researcher (female) who sets off into the Amazon jungle to find the remains and effects of a colleague who recently died under mysterious circumstances.” But she never wrote it, and in due time her idea went away and settled in the brain of another writer, Anne Patchett, who actually wrote that story, which she titled “State of Wonder”. These writers met and kissed, or something, and became best friends.

This story of course sounds too good to be true, but even if it isn’t, there’s a lesson behind it, which is more or less that there are only so many ideas floating around the universe and if you don’t write your novel, someone else will.

Clueless Murakami

Before starting Murakami’s huge (970 pages, good lord) new novel Killing Comentadore, I read Men Without Women, a slight book of short stories told to the narrator Murakami by men, some of whom are friends, others acquaintances, all of whom are currently living without women. Some of them care, some of them don’t, and some are suicidal or dead, but what they have in common is that they are more or less clueless about the women who have vanished from their lives. The Murakami girl is either a superhero (1Q84) or she disappears never to be seen again.

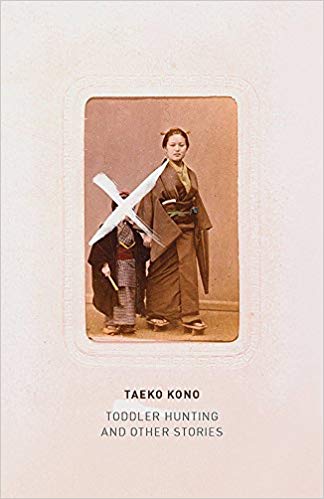

Taeko Kono is one of them. And she’s nasty:

Rachel Cusk et al vs Don Quixote

After coming to the end of the delicious, rapturous, repetitive, raving, magnificent most-engaged-knight-in-the-entire-world Don Quixote, I’ve become obsessed with Rachel Cusk’s trilogy; Outline, Transit and Kudos. She’s the anti-Cervantes, the “dissociate artist for a dissociate age, asking from the back seat; ‘is this real life?'” So writes Patricia Lockwood in the London Review. Like so many others, I started off disliking her, and still do, but I read on.

Probably it’s the Voice. It drones seamlessly from one person’s story into the next, commenting when it feels like it, then going on to the next like a distracted, OCD dog. The voice is monotonous, without nuance. At times, it’s indistinguishable from the person it’s supposed to be conversing with. You get the sense that the Voice listens, but that it can only respond to what mirrors itself in the teller’s stories. When the Other Voice, the one telling a story (mostly men strutting their stuff) stops for breath, the Cusk Voice comes out like the cuckoo in the clock, presents its rebuttal, or its insight, which are at times so embedded with “it seems to me” and “in a kind of way” and “perhaps” as to be unfathomable, pretentious, as if ones point of view is the only proper response to a story being told by someone else.

Lorrie Moore says this: “We see that we are experiencing a presentation: a midair collusion of storytellers and pronouncers. Faye’s voice and those of the characters she encounters sometimes merge—and that is the point. However underperforming our lives may be, the stories of them are always performances. Faye makes statements that seem to announce the book’s narrative strategy: “I was beginning to see my own fears and desires manifested outside myself, was beginning to see in other people’s lives a commentary on my own.”

The Voice is hypnotic. I’m mesmerized. Cusk is traveling, and her fellow travelers are as mundane as mine are.

I’m also reading Sigrid Nunoz, The Friend, Houellebecq’s Submission and I’m paging through Karl Ove to see if it’s possible to commit to The Struggle, which I’ve been saving for when I’m convalescing from flu. Strangely, I find no pleasure reading these authors. With some exceptions, mostly their sentences ring pithy as hammers banging through rock, stripped of imagery, lacking sensuality, self-involved with their own drama. And yet, and yet – they are driven, relentless, trance inducing.

I came to Cusk late because along with Sheila Hati and Claudia Day (whose recent article in the Paris Review begins with “I wrote the first draft of my novel Heartbreaker in a ten-day mania in August 2015” – I’m supposed to want to read this?) she was part of the New Motherhood, what it means, what price you pay, how to write a novel with children hanging from your clothing sucking your blood. I admit that the topic doesn’t interest me, I simply don’t care; the topic brings out the worst in me, the me that says, Yes, giving birth is a big deal, yes domesticity is the death of freedom, yes, it is the birthing of the death of another and yes, it’s also a big deal to write a novel while a mother. Yes yes yes, there are consequences for everything, get over it, find something else to write about. Aside from Patty Smith and Keith Richards, who have a ball writing about their =interesting, demonic lives, I can’t think of a memoir worth writing.

What it boils down for me to is this: Everything in life is someone’s drama, and eventually, unless it is transformed into language, paint, color, rhythm, movement, conversation; story; into beauty, it feels like just one more voice grinding away in the background with the clothes dryer.

Which, if you’re DeLilio, or Robert Altman and maybe Rachel – well, drone on.